Why a birthday tribute to Roger Ebert? You know, the Pulitzer Prize-winning syndicated film critic and author of a kajillion books and screenplays and Forbes’ most powerful pundit in America and television movie criticism pioneer and film scholar and educator and winner of the Peter Lisagor Award for Arts Criticism and too many other honors to mention?

|

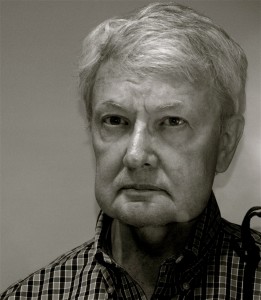

| Roger Ebert (Self-Portrait, 2006) |

I can think of four reasons.

One, he has the wit and charm of Oscar Wilde.

Two, he has the encyclopedic knowledge of the imdb.com. (The professional version, not the free one.)

Three, he has the stamina of a marathon runner.

Four, he has — when it comes to star ratings — the generosity of Santa Claus.

Wait!

Now that I think about it, a fifth defining element describes Roger Ebert, perhaps even better than these previous four.

Fearlessness.

Utter, absolute, ridiculous fearlessness.

We all saw this quality after the Sun-Times film critic underwent surgery for a cancerous growth in his mouth. The operation removed part of his jaw, took away his power of speech, radically altered his physical appearance, and even affected his ability to walk.

When the time finally came for Ebert to climb back into the saddle (that would be his row-end seat at Chicago’s Lake Street Screening Room) and return to public life, his friends, relatives and all the people who cared about him shouted in unison: “Don’t do it, Roger!”

“They will make fun of your appearance!” they warned.

“You’ll be the butt of jokes on late-night TV!” they screeched.

“People will be mean to you!” they asserted.

Ebert said, so what?

Then he wrote stories about his fight with cancer, and published unflattering photos of his post-surgery self, accompanied by a line borrowed from a Martin Scorsese movie: “I ain’t no pretty boy no more.”

See?

Utterly fearless.

He went on to bust down a dark door of societal perception so that others less confident about their physical afflictions might feel more accepted in public.

Long before his medical problems, Roger Ebert forged a reputation for standing up for himself, and, in a display of his strong Midwestern roots, standing up for others, regardless of the cost.

I am reminded of the time when the Darth Vader of the Sun-Times empire, Conrad Black, dispatched an e-mail to Ebert expressing indignation that the newspaper’s film critic would dare to bite the hand that feeds him, and feeds him quite well.

How well?

In the e-mail, Black mentions the $500,000 the Sun-Times pays its film critic, a fortune for any newspaper journalist writing about the arts. Black chastises his critic for accepting his salary, then publicly attacking his boss for such things as failing to maintain the Sun-Times building and treating his employees properly.

(Note to Conrad Black and all others who worship money: You can pay Roger Ebert, but you’ll never buy him. He’s the Eliot Ness of Chicago Film Critics.)

I received copies of Black’s e-mail from friends probably nanoseconds after it became public. But who leaked it? And why?

It didn’t take Woodward and Bernstein to deduce that Black, or one of his minions, dropped the e-mail into cyberspace. Again, why?

My best guess: to publicly undermine Ebert. By releasing his astronomical salary to the world, Black’s forces sought to turn public opinion against him by portraying him as an ungrateful rich guy.

It backfired.

When I was pressed for a response to this e-mail, I knew exactly what needed to be said: Roger Ebert is the Sun-Times employee with the most to lose, yet he’s the first one out there in the trenches fighting for the rank and file.

See?

Ridiculously fearless.

This memo, circulated to the Chicagoland film critics’ community, reaped an unexpected benefit for me. It warmed up a two-decades-old frosty relationship between us.

Tragically, for two decades, Ebert and I sported black-and-blue spots where we had been touching each other with 10-foot poles. I always felt nervous and uncomfortable in his presence. He always seemed to be wary and edgy in mine.

What was it? Natural friction between an only child and a firstborn? The suspicious natures of journalists working for competitive newspapers? I don’t know. It doesn’t matter.

From that moment, the invisible glacier between our back-row seats in the Screening Room instantly melted away. We have since become professional friends, and upon occasion, even allies.

(Ebert might remember everything quite differently than I do. But that’s what his blog is for.)

Now, lest you think that this birthday tribute is just a fawning salute to a Chicago institution, I said he was fearless. Not flawless.

After all, Santa Ebert gave four stars to Alex Proyas’ mystery thriller “Knowing,” about a 50-year-old numerical chart that predicts global disasters — but only the ones that occur within a convenient driving distance for Nicolas Cage.

Yet, Ebert trashed David Lynch’s 1986 masterpiece “Blue Velvet,” one of the 10 greatest motion pictures of its decade and part of Hollywood’s infamous “van Gogh Trilogy” along with “Reservoir Dogs” and “The Fly.” (Just kidding.)

I discovered Ebert’s prolific writings as a Communications major at Eastern Illinois University in downstate Charleston. I noticed right away Ebert didn’t write like the critics from New York and Los Angeles. His reviews were bold and direct, and, yes, courageous in their analysis. I marveled at the way he custom-crafted leads to capture the essence of each movie he wrote about. Most critics lecture. Ebert prefers to discuss.

In 1975, Ebert teamed with his Chicago Tribune nemesis, the late Gene Siskel, to review movies on television as the hosts of PBS’ “At a Theater Near You.”

Neither critic conformed to TV executives’ idea of a telegenic presence. Ebert went on the air with his large horn rim glasses atop a much larger body than he has today. Early on, one critic referred to him as “a block of concrete with headlights.”

Fearless?

Oh, yes, because common TV “wisdom” said that regular-looking print journalists didn’t belong in broadcast, a business run by hair gel and Q-factors. Ebert and Siskel broke down another door by being their print journalist selves, not manufactured TV entities.

Ebert’s most recent brush with fearlessness came much slower, as he transcended the boundaries of film criticism and evolved into Forbes magazine’s “most powerful pundit in America.” He earned the title by providing informed and passionate insights into current events, and by taking on mass media ideological bullies and professional dimwits.

As you read these very words, somewhere out there in Chicago and the world, Roger Ebert continues to bust down doors like Eliot Ness on a hooch raid.

Not bad for a guy who can’t talk and walks a little funny.

And if we ever get up a game of Charades, I want to be on his team.